Editor’s note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service, under the headline “Q&A: How Did the U.S. Patrol the Caribbean for Drug Smuggling Before It Started Blowing Up Boats?” Subscribe to their newsletter.

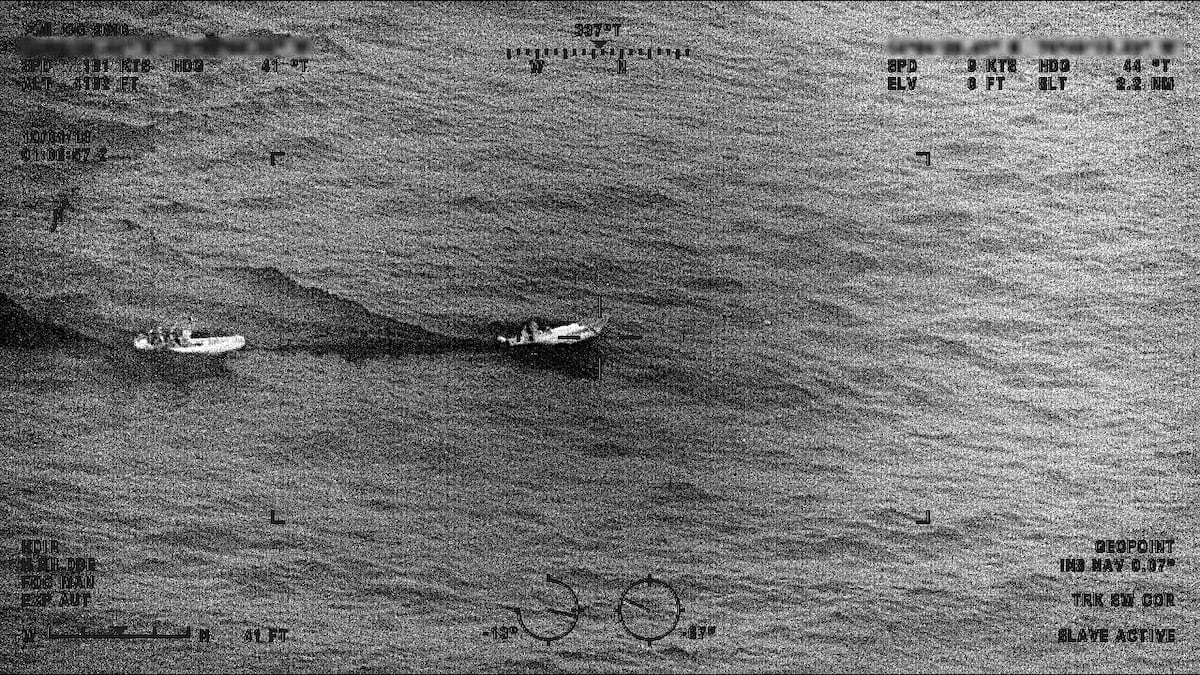

For decades before the Pentagon started blowing up alleged drug boats in the Caribbean, the Coast Guard tracked, intercepted and boarded the little skiffs that carried cocaine and marijuana across the Caribbean and eastern Pacific to the U.S.

The dramatic escalation this fall, which has killed at least 99 people as of Wednesday, including 12 this week, raises questions about the legality of the strikes — and also overshadows the strange reality that the Coast Guard is continuing its long-standing counterdrug patrols, making record cocaine seizures while often simply returning the crews of drug boats to their home countries.

The Coast Guard’s counternarcotics operations have always been seen as primarily law enforcement work, built on careful legal protocols and international cooperation. It’s a stark difference from the Defense Department’s new approach, which considers drug runners in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific Ocean to be “enemy combatants” and targets boats with weapons of war.

To understand what’s at stake — and just how much of a shift these airstrikes are — The War Horse spoke with several experts: Brian McNamara, a professor at Tulane University’s School of Professional Advancement and a retired Coast Guard JAG officer; Mark Nevitt, a professor at Emory University’s School of Law and a retired Navy JAG officer; and Kendra McSweeney and Mat Coleman, Ohio State University geographers who have studied at-sea drug interdictions.

“The understanding was always that the Department of Defense would assist,” McSweeney says, “but never directly participate.”

Q. How has the US typically dealt with drug smuggling boats on the high seas?

A. Countering illegal drugs on the ocean has long been the Coast Guard’s job. The Coast Guard is a branch of the military, but it’s also a law enforcement agency — meaning it has the authority to board certain vessels and detain suspected drug runners.

Coast Guard teams receive permission through standing legal agreements to board certain boats, seize any contraband and transport suspected smugglers back to the U.S. for prosecution. It’s a well-oiled operation governed by longstanding legal conventions and international agreements — and honed by years of experience battling smugglers on the high seas.

“The Coast Guard was intercepting rumrunners out of Cuba during Prohibition,” McSweeney says. “[They’ve] been the at-sea police for a long time.”

Q. So the other military branches aren’t involved?

A. Until this fall, the rest of the military only played a supporting role in counterdrug work. The military, along with other agencies and partner countries, share illicit drug intelligence, and the Coast Guard uses that intelligence in its interception work.

Navy ships — both our Navy and other countries’ — have also traditionally supported the Coast Guard’s work. Because it’s not a law enforcement agency, Navy sailors cannot board another vessel at sea. But Coast Guard teams deploy aboard Navy ships and board suspected drug boats from there, using the Navy’s bigger footprint on the ocean to supplement the Coast Guard’s older, smaller fleet.

“The Navy [has] capabilities and frigates, destroyers and a whole slew of vessels that can sort of supplement and supercharge this mission,” Nevitt, the retired Navy JAG officer, says. “But the Coast Guard is taking the lead.”

Q. So can the Coast Guard just board any boat?

A. No. The ocean is a very big place, governed by a complex web of laws. The primary maritime agreement at play is the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, which outlines what countries can and can’t do on the ocean, both in international waters — about two-thirds of the Earth’s oceans — as well as in territorial seas, which are closer to land and controlled by coastal countries. The U.S. isn’t a signatory of the convention, but it tends to follow the rules the convention lays out, considering it customary maritime law. The U.S. also has its own federal laws governing the Coast Guard’s authorities.

Those rules govern which boats the Coast Guard can and cannot board. It’s complicated, but basically the Coast Guard can board any boat in international waters that doesn’t claim a nationality — in effect, a “stateless” boat. The Coast Guard also has other international agreements and protocols that help it obtain permission to board boats in many other countries’ waters or certain boats flying other countries’ flags.

Q. How does a Coast Guard drug boat interdiction work?

A. Coast Guard ships, called cutters, patrol areas where drug smugglers tend to operate — like the Caribbean and eastern Pacific. They receive military intelligence, both domestic and foreign, to clue them in to the path of suspected drug boats.

“All nations will sort of work together to halt the trafficking of drugs,” Nevitt says. “It’s not just a U.S. problem, it’s a global problem.”

Once a Coast Guard cutter has identified a potential target, it turns to an escalating “use of force” protocol, using verbal warnings and warning shots before shooting out the boat’s engines and approaching with a boarding team. The intent is to stop the boat — but to avoid injuring the people onboard.

“There was a lot of training and competency development amongst all of the Coast Guard members who were involved in that kind of dance,” says McNamara. “[The smugglers] were more valuable alive than they were dead.”

Q. So who are those smugglers the Coast Guard picks up?

A. McSweeney, along with her collaborator Coleman, has built a comprehensive database of legal cases stemming from Coast Guard drug interdictions. They found that the drug smugglers the Coast Guard detains in the eastern Pacific and the Caribbean are typically running cocaine or sometimes marijuana — almost nobody is smuggling fentanyl.

“Fentanyl is a terrestrial product,” Coleman says. “It’s made on land and transported on land.”

Most drug boats are crewed by just three or four people, who tend to be pretty economically desperate, McSweeney and Coleman say. They’re often coerced into doing this work, running open-air pangas, laden down with multiple outboard motors, through heaving waves on the open ocean. Those who volunteer get only small paydays. And they’re not typically cartel members.

“They’re basically the Amazon driver delivering the package,” McSweeney says. “They’ve just been hired to drive the drugs.”

Q. Does the Coast Guard find drugs on every boat it boards?

A. No. Not every suspected drug boat the Coast Guard intercepts turns out to be smuggling contraband. In a memo from this past October, the Coast Guard commandant wrote that nearly one in five of the boats it boarded over the last year did not have drugs onboard. That number holds steady for boats intercepted off the coast of Venezuela — where several of the airstrikes have been focused.

Q. What happens after the Coast Guard detains a smuggling crew?

A. Until this year, the Coast Guard would often bring alleged smugglers back to the U.S. for criminal charges and prosecution. But the real value, McNamara says, was in the information these low-level operatives could provide.

“It helped the U.S. gather intelligence on who these drug smugglers were and helped build from the ground up a picture of what the cartels were doing,” he says.

But that changed this past winter. In February, Attorney General Pam Bondi released a memo outlining the Department of Justice’s priorities in investigating and prosecuting cartel operations, writing that the department would “rarely” prosecute low-level offenders — including those intercepted at sea — to free up resources for bigger investigations. The Coast Guard now typically returns them to their home countries.

Q. So has the Coast Guard stopped intercepting drug smugglers?

A. No. In fact, the Coast Guard has been surging its ships and aircraft to the Caribbean and eastern Pacific, leading to record-breaking drug busts.

“In cutting off the flow of these deadly drugs, the Coast Guard is saving countless American lives,” Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said after the Coast Guard announced it had seized more than 100,000 pounds of cocaine in the eastern Pacific between August and October this year.

Q. How are the smugglers the Coast Guard intercepts different from the alleged smugglers the Defense Department is bombing?

A. As far as experts know, they’re not. During the exact same time frame that the Coast Guard seized those 100,000 pounds of cocaine, the Department of Defense, through its Special Operations Command, began its airstrike campaign. After the first strike, State Secretary Marco Rubio said that Trump could have ordered the alleged drug boat be intercepted — but instead chose to bomb it.

“Instead of interdicting it, on the president’s orders, we blew it up,” Rubio told reporters.

Q. So what does this mean for the Coast Guard’s work?

A. In spite of Noem’s praise, President Donald Trump bluntly told reporters last month that the Coast Guard’s approach has been “totally ineffective.” A Department of Homeland Security Inspector General report from earlier this year found that the Coast Guard hadn’t met its own drug seizure goals in the past, in part because cutters were unavailable for patrols and seizure information wasn’t always accurately recorded.

This year, however, the Coast Guard announced it had seized more than 500,000 pounds of cocaine, well over three times the amount it usually intercepts in a year. But the experts we spoke with said that in the long run, the airstrikes will likely make the Coast Guard’s work more difficult. Countries that previously shared intelligence with the U.S., like Britain and Colombia, have said they will no longer cooperate on counternarcotics work over fears that the U.S. is violating international law.

The Coast Guard’s counterdrug approach was built on international collaboration, governed by legal agreements and mutual trust built up over decades, McSweeney says.

“That is literally being blown up with every strike.”

This War Horse news story was edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.

Read the full article here