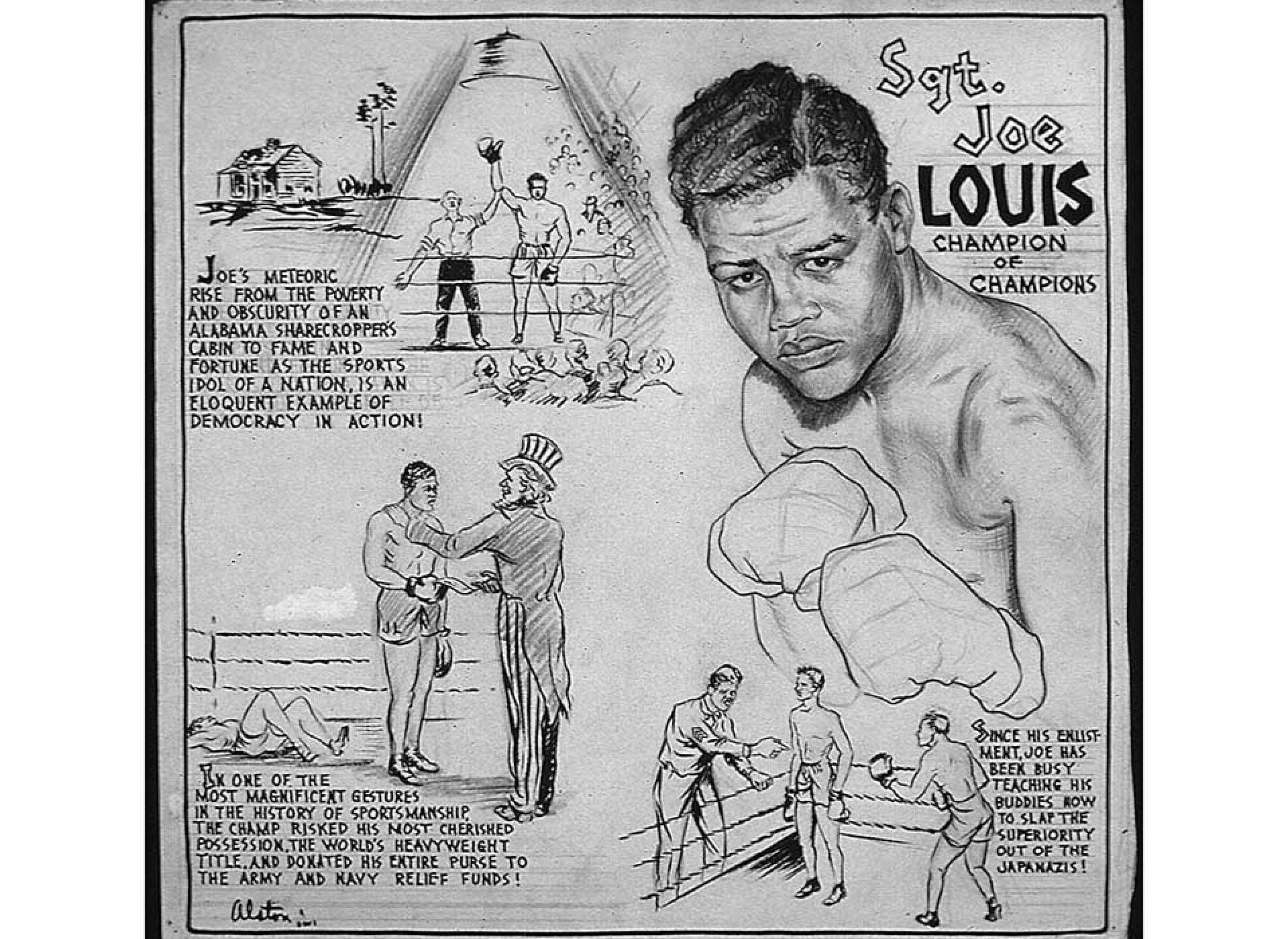

For 12 years — longer than any fighter past or present — Joe Louis would be the undisputed king of boxing. So dominant, in fact, that the “Brown Bomber” transcended the stringent racial barriers of 20th-century America, cheered on by both Black and white citizens.

Louis, the grandson of a slave and the great grandson of a slave owner, rose to prominence in 1930s to become the face of freedom and democracy when he faced off against Germany’s Max Schmeling in 1938. According to the National African American History and Culture Museum, “It was reported that Hitler called Schmeling just before the fight and ordered him to win for the sake of Nazi Germany.”

The match was more than a test of will between two men — it had become a battle of warring ideologies. Louis won.

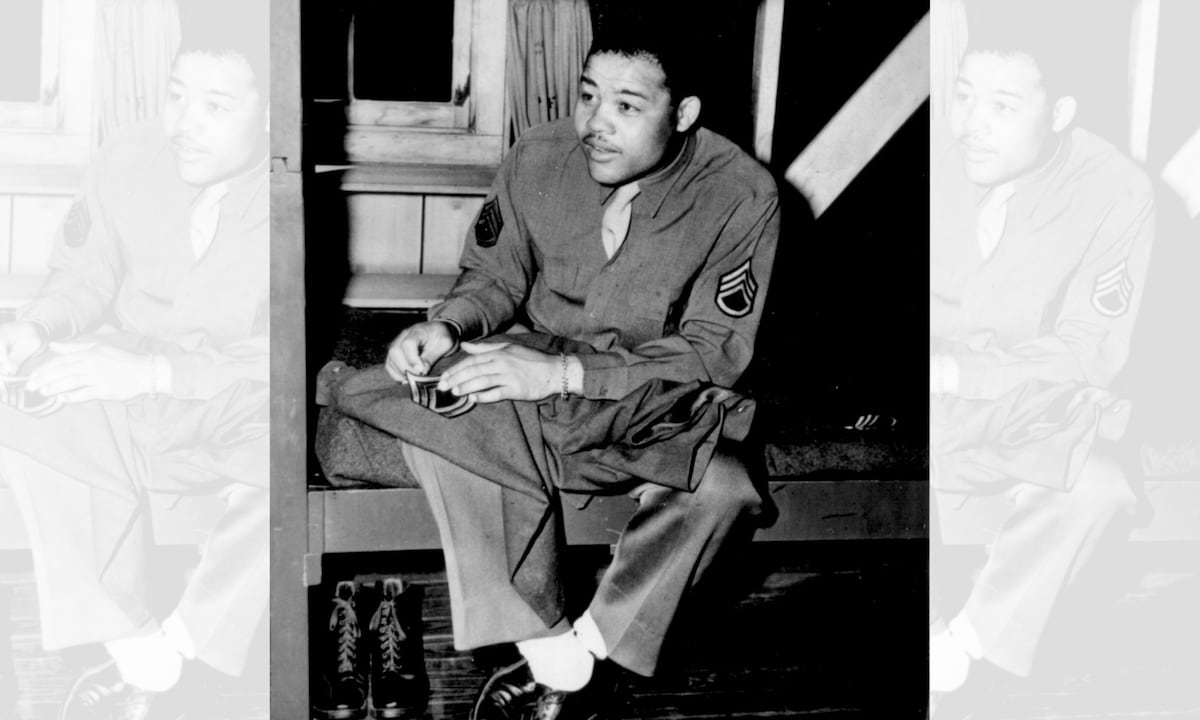

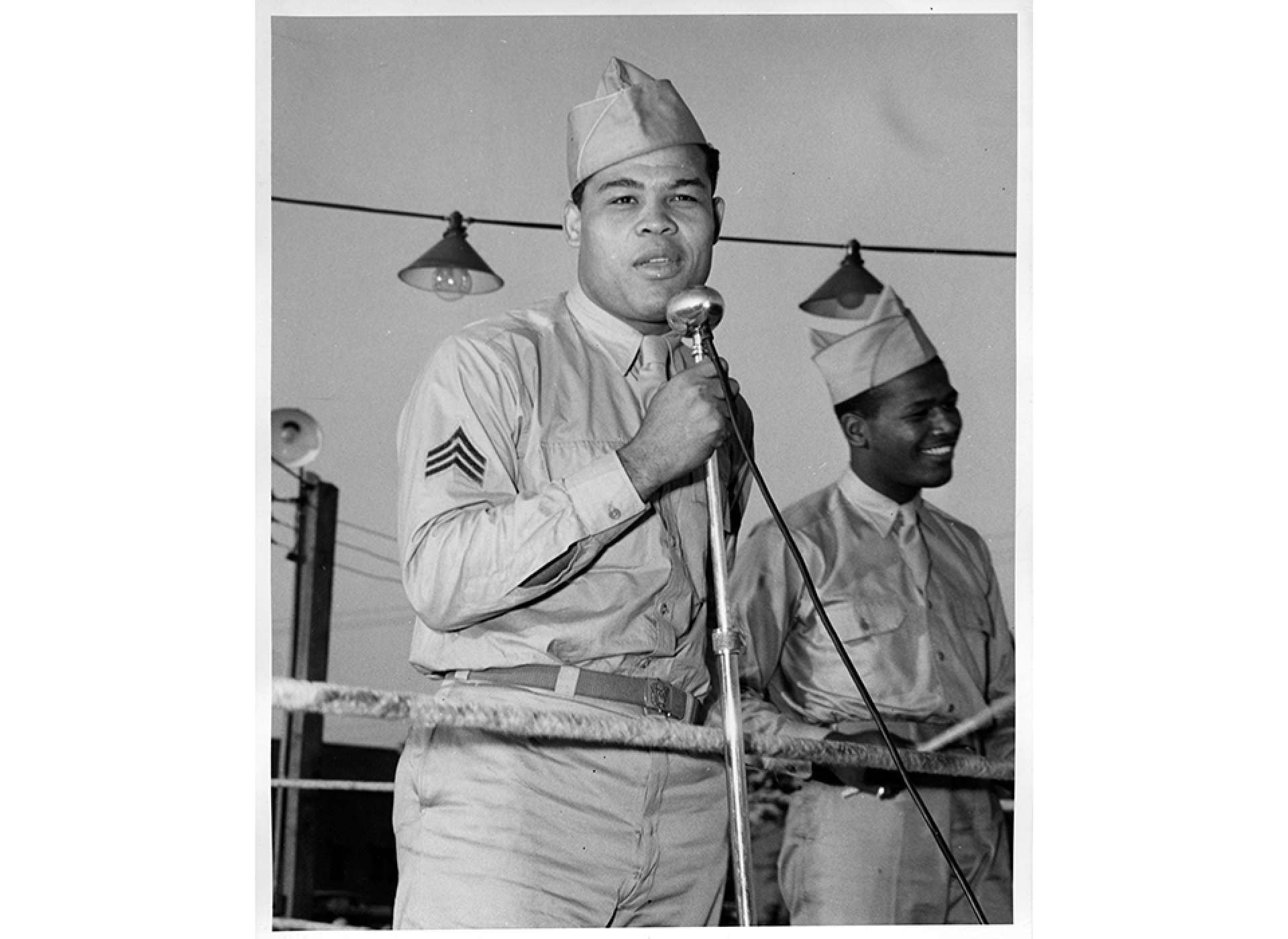

Louis enlisted in the Army in 1942, rising to the rank of sergeant. Kept stateside, he fought in hundreds of exhibition matches to entertain the troops and raise money for the military.

But, according to authors Johnny Smith and Randy Roberts, Louis’ service and his contributions to the civil rights movement have largely been glossed over. Their latest book, “The Fight of His Life: Joe Louis’s Battle for Freedom During World War II,” hopes to remedy that dearth of material.

Johnny Smith recently sat down with Military Times to discuss Louis’s evolution from boxer to a champion for Black Americans. The below interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Military Times: Sports have long been a successful platform for protest. How did Joe Louis contribute to that legacy?

Johnny Smith: That gets to the heart of the reason we wrote the book. Joe Louis, in most biographies, the sections that deal with his service during World War II … I don’t want to call it superficial, but it’s not treated with the real depth and importance that Joe Louis played during the war.

In 1938, it’s the biggest fight in the history of the world, when Joe Louis steps into the ring at Yankee Stadium and he knocks out Max Schmeling, who was viewed as a proxy of the Nazi Party and Adolf Hitler. Like Jesse Owens winning four gold medals in Berlin in 1936, Joe Louis becomes a symbol of not just Black America, but of democracy — opposing totalitarianism, opposing Nazism. That was a powerful moment that made Joe Louis the most famous American athlete in the world, Black or white.

Louis is the heavyweight champion from 1937 to 1949, and the heavyweight championship gives him a platform. In 1938, he’s a symbol.

In most books that focus on Louis it’s almost as if he’s stuck in 1938, but we see two things change for Louis in our research: Number one, in 1940 he’s recruited by the Republican Party to endorse Wendell Willkie. Joe Louis gives a series of speeches in Northern cities where he explains why he’s for Willkie and why he’s opposed to Franklin Roosevelt, the Democrat.

He criticizes the Democratic Party for failing to pass a federal antilynching law. He criticizes the Democrats for failing to protect the civil rights and voting rights of Black Americans. On the other side of that is Jesse Owens, stumping for Franklin Roosevelt. This was a pivotal moment where, for the first time, the two big political parties are seeking the endorsements of Black athletes.

This was crucial for Louis because before this he’s a bit shy with the press. He had to overcome a childhood stutter, he could be a bit uncomfortable around white reporters, but he develops a confidence in his public speaking, and he also develops a political consciousness. So in 1940 that’s really a turning point.

The second thing is the war itself. When the War Department drafts Louis as an ambassador for promoting goodwill during the war, what’s happening is he travels to dozens of camps. It changes the relationship that Louis has with his fans, because these are Black men who are serving to fight for democracy abroad but also at home.

At different moments he challenges segregation and discrimination against Black soldiers, and he realizes ,‘I have to be more than a boxer. It’s not enough to be the heavyweight champion. Being a Black heavyweight champion has not expanded democracy for my people.’ He has to take action.

MT: Can you talk about the evolution of Louis’ rivalry with German boxer Max Schmeling?

Smith: I think the big thing to understand about Louis is he truly was a man of the people. He would talk to anyone; he would help anyone he could. There’s all these stories about him giving the last dollar bill in his pocket to some guy in Harlem. It was part of the image of him. My point here is that Louis didn’t necessarily see Schmeling as the perpetrator of evil or anti-Semitism. But I’m not sure when the friendship really begins. It’s certainly not during the war, because Louis talks a little trash — saying how he’d like to be out there on the battlefield and take out Schmeling.

But there’s a clip of the show “This is Your Life” starring Louis. Schmeling shows up. [Louis cracks a smile and enthusiastically hugs Schmeling.] They both risked their lives in the ring. They both served in a horrific war. They were representatives of their government and so they did have much in common.

MT: What was Louis’ evolution regarding his views on fighting for civil rights?

Smith: I think one part of the story that’s worth highlighting is the fact that although Joe Louis was born in Alabama, he’s a product of the urban North. He comes to boxing in Detroit, Chicago. For much of his career Louis is fighting in New York City. The furthest south he ever had a match was Washington, D.C. Most of his fights were above the Mason-Dixon line.

As a heavyweight champion of the world, he enjoyed a certain kind of freedom and mobility that few Black men did. But when he goes into the Army — we have to understand that the Army policy was essentially replicating the Jim Crow South system — that includes Louis. So now he’s confined in ways that he had not been before the war. During a troop campaign, Louis along with Sugar Ray Robinson go to all these military bases, many of them in the South. He’s being confronted with conditions that he had not had to face in his boxing career.

It’s in these military camps that Black soldiers are complaining that they’re being treated like prisoners in a labor camp. That they are being harassed, tormented, facing abuse. There are violent clashes in these camps. He witnesses this; he hears stories about it. And I think that the big turning point that we, wrote about at length, comes in 1944.

MT: Louis and Robinson famously developed a friendship during their time in the Army. How did that come about?

Smith: It’s a mutual admiration. Jackie Robinson was a big football star at UCLA, so they knew of each other, certainly, they could relate to each other. They’re both Black men living in a segregated sports world.

But when Jackie Robinson is serving at Fort Hood in Texas, and a white bus driver tells Robinson you better get to the back of the bus, Robinson remembers that Louis took a stand against segregation, he recalls the courage of Joe Louis and says, ‘No, I’m not going to do it.’

There is a link that has been overlooked between Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson. We remember Jackie Robinson for being outspoken in terms of civil rights. We don’t remember Joe Louis in the same way, but it was Joe Louis who gave Jackie Robinson the confidence to take his own stand.

MT: Is there anything that particularly surprised you in your research?

Smith: What I love about this book is there’s a lot of archival material in it and we knew that the only way we were going be able to write something new was to go to the archives. The newspaper coverage was going to be critical and following Louis day by day, week by week, in his travels, but the archives allowed us to tell the political story.

The other thing, too, that I think about in terms of archival sources has to do with Sugar Ray Robinson. We obtained his military file and it was full of reports from doctors assessing whether or not he had some kind of brain trauma from boxing or he suffered from amnesia, and that’s why he couldn’t recollect what had happened to him right before they’re supposed to go overseas. No one has ever written about this in detail. The only sources that existed previously were Sugar Ray Robinson’s memoirs, which contradict some of these documents.

Those documents in his military file allowed us to better understand his family history, his history with these headaches and the difficulty the doctors had coming to a conclusion about what was causing the headaches. It makes for a fascinating case.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here