By 1942, as the United States plunged headlong into a world war, many men found themselves in far-flung places with names soon to enter the American lexicon: Guadalcanal, Anzio, Bastogne.

The logistics for transporting troops and war materiel was a dizzying hurdle to overcome for Allied leaders. So too was the ability bring the tastes and smells of home to millions of servicemen shivering in foxholes in Europe and sweating in the sands of the Pacific.

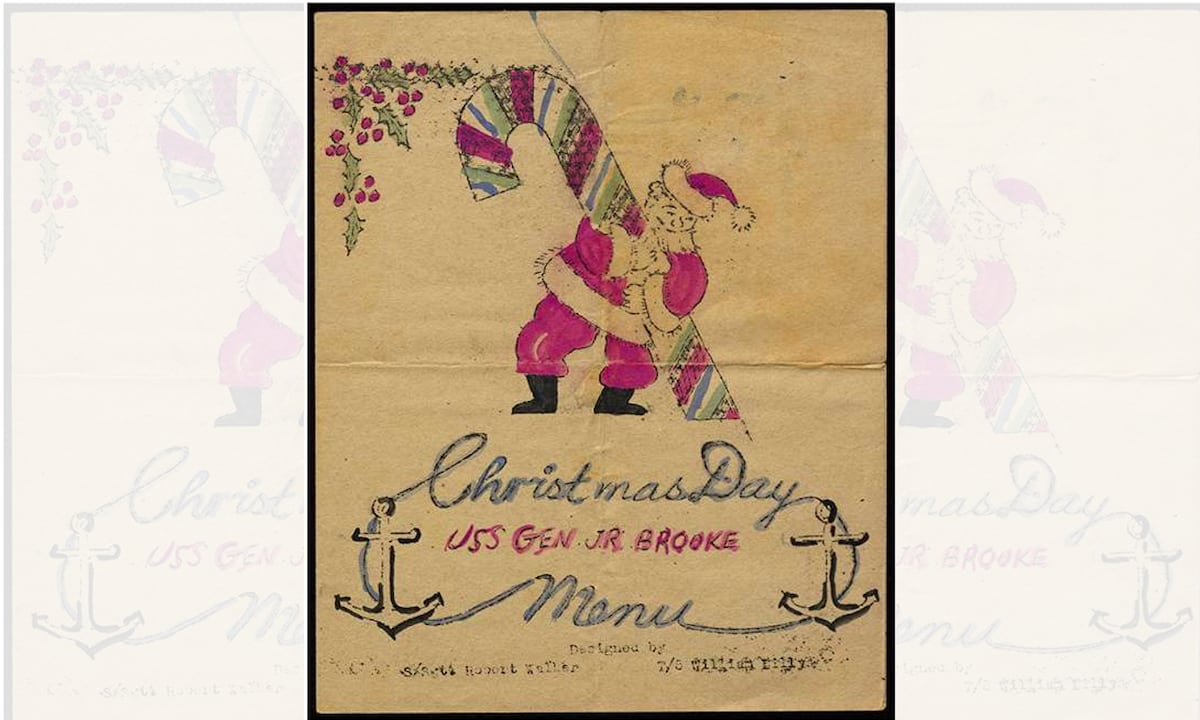

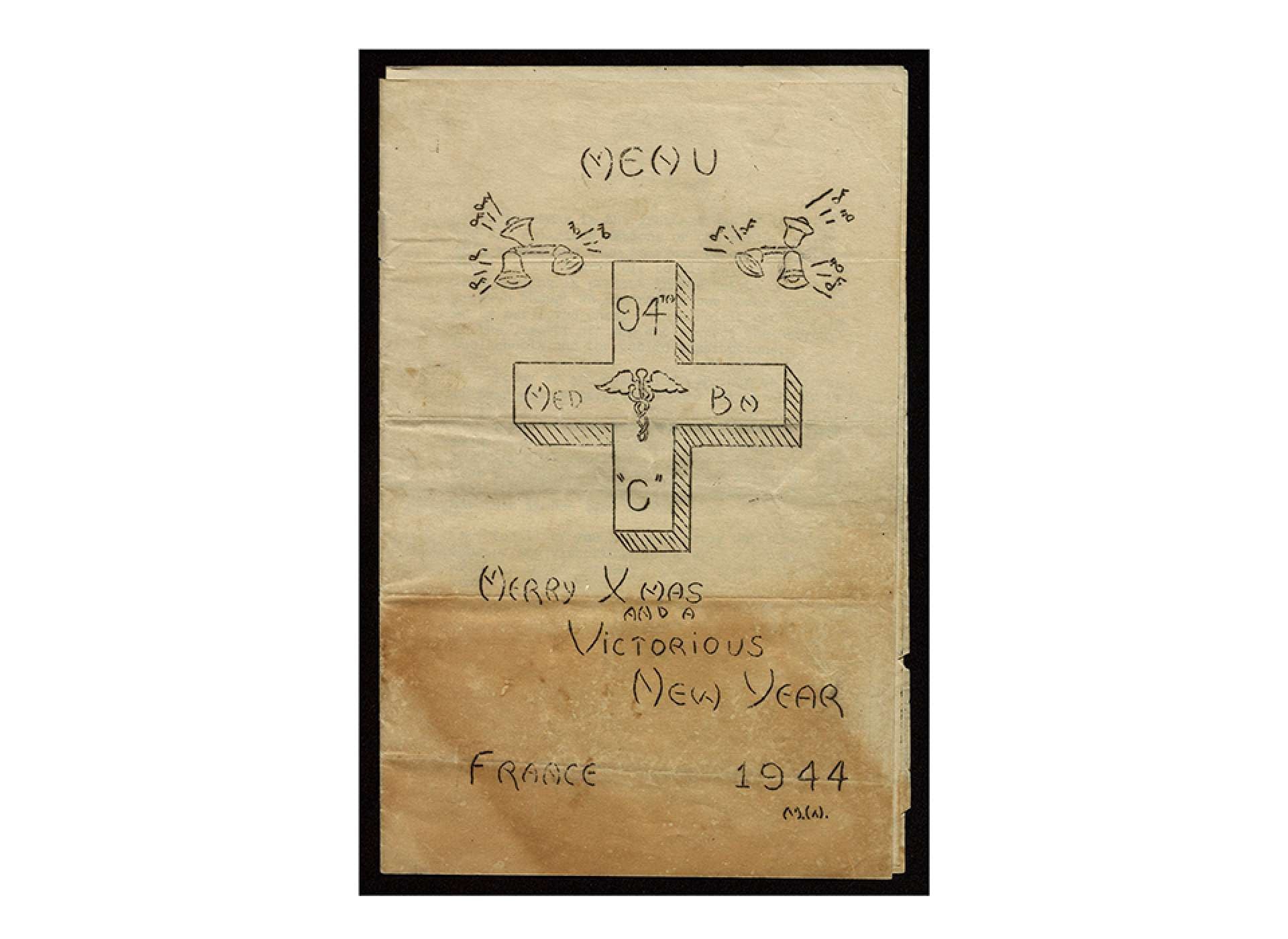

Today, the National WWII Museum is home to a myriad of ephemera showcasing the logistical feat of Christmas abroad, with special hand-printed and illustrated menus created by American POWs in Europe and the Pacific and those across the services.

The menus showcase traditional fares — such as turkey and potatoes (dubbed Snowflake Potatoes, which was a mixture of potatoes, cheese, sour cream, butter and chives) — and less traditional fares such as cigarettes and cigars.

Where one was stationed would also impact Christmas meals, where local elements were often included, according to Kim Guise, senior curator and director for curatorial affairs for the National World War II Museum.

“I was looking at a menu from Christmas 1941 in Hawaii, you know, just weeks after the attack [on Pearl Harbor]. Now, sometimes these menus were printed in advance… but one of the courses is pineapple, cheese and cold pineapple juice. So that’s not something that you would see in England.”

The power of a hot meal — and presents — could galvanize morale, something understood by Allied leaders from the top down.

“It’s interesting,” said Guise, “the power of certain things to transform and experience. People wrote about how receiving Christmas packages and mail, in particular, how that could make you feel.”

Many men brought back trophies of the war: flags, guns, different ephemera. But they also brought back playbills and menus.

“I think that in itself tells us something about that time,” said Guise. “Those were important moments, important meals that were treasured and thus the menus themselves were saved.

“The richest source of information about that time is correspondence, personal correspondence,” Guise continued. “Almost nearly every letter talks about food in some kind of way. They talk about receiving food from home, so that was one way in which people went off script, I guess, or supplemented what they were receiving [from the military].”

The menus and letters now in the museum’s collection showcase how people, even in the disoriented circumstances of war, hold on to fragments of normality.

And despite the omnipresent threat of death gnawing at soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines, the societal pressure to uphold Christmas traditions — namely not opening presents until Dec. 25th — was still present, most of the time.

One soldier, Guise relayed, had received a package from home early, and was doing his best to hold out until Christmas morning.

The man was unable to hold off, writing to his family “the temptation was too great. I was in the mood for a midnight snack, so I opened one of the Christmas packages.”

Inside he found three cans of Vienna sausages.

“My face dropped to the floor,” he cheekily wrote to his family. “If there’s anything we hate over here besides SPAM, it’s Vienna sausage.”

During the war, families of service members were instructed to mail Christmas packages to their loved ones between Sept. 15 and Oct. 15, but, just like logistical struggles today, even that was no guarantee for delivery.

“Even now everyone’s familiar with the holiday rush and the mail, how that impacts transportation,” Guise relayed. “Think about that in wartime, in a global war. … Sometimes they would receive it in October and sometimes they would receive it in February.”

Yet despite the erratic timing of hot meals and goods from home, they played a crucial role in soldier morale.

The museum, according to Guise, has thousands of these festive moments recorded and remembered for posterity.

One airman, from the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, who had been shot down in Aug. 1943, and held in Stalag Luft 17, near Krems, Austria, wrote to his sister on Dec. 26, 1943:

“Another Christmas come and gone. Not much news today. Feeling fine, spirits high. No mail is yet from home. … I suppose you have your tree this year, with the kids having a picnic. I sure miss little Cookie. Tell everyone I said hello.”

Then, on Dec. 25, 1944, the same airman writes to his sister, alluding to delays in communication:

“Christmas number two has come again. I hope number three will be in CL [Center Line, Michigan]. I am still in good health. Hope everyone is likewise there. Please extend my Christmas greetings to all. Write with news when you can. Merry Christmas. Happy Easter.”

Another soldier wrote home that “considering the circumstances” he had had the best “Christmas possible,” gleefully proclaiming that he had received two “delicious” Pabst Blue Ribbon beers.

While the holiday season amplified the extreme deprivation, fear and loneliness for many, the brief respite shows, according to Guise, “how people in very difficult circumstances hold on to these little moments.”

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here