It was a miracle of deliverance.

Orders had gone out to military officers to collect “every kind of watercraft … that could be kept afloat and had either oars or sails,” to slip roughly 9,000 men across the water to safe harbors and away from a much larger, determined enemy.

Except this retreat was not in 1940. There was no Vice Adm. Bertram Ramsay feverishly stringing together Operation Dynamo to extract 338,336 soldiers — most of whom made up the bulk of the British Expeditionary Force — from ignominious defeat at the hands of the Germans at French port of Dunkirk.

The year was 1776 and the enemy was the British.

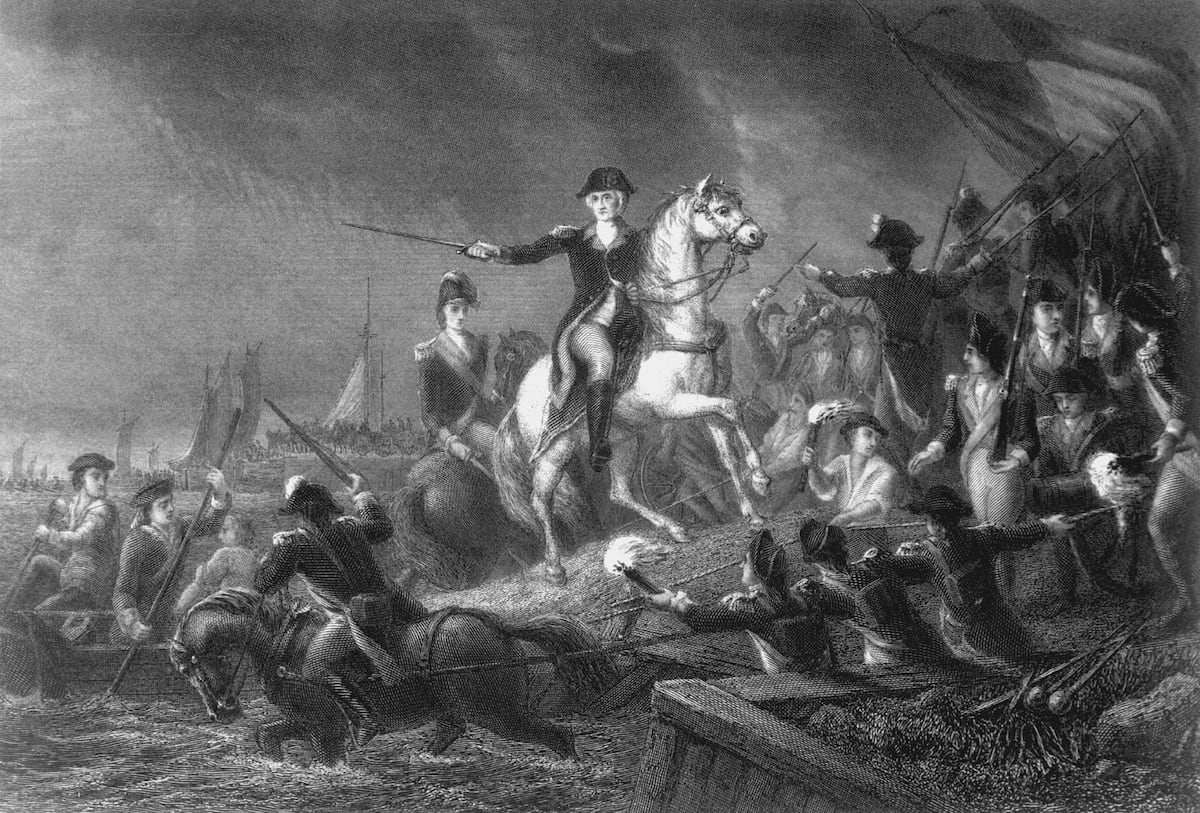

Wars are not won by evacuation, but Gen. George Washington’s decision to evacuate Long Island and retreat to Manhattan in August 1776 ultimately saved the Continental Army and the patriot cause.

Battle of Long Island

After its evacuation of Boston in March 1776, the British, as Washington accurately concluded, would set their sights on New York. The only question was when.

By mid-April, Washington had marched his 19,000 soldiers to lower Manhattan. And there they waited. Through the spring, and then into summer.

It wasn’t until early July that 400 British ships with 32,000 men commanded by Gen. William Howe arrived at Staten Island, according to Mount Vernon. When Howe offered a pardon to the rebels, Washington answered, “Those who have committed no fault want no pardon.”

Still, they waited.

While Washington was convinced that the British would attack Manhattan, he continued to fortify Brooklyn, just across the water’s edge.

“They mean to land the main body of their army on Long Island and make their grand push there,” Washington wrote to John Hancock.

Yet his failure to secure the rarely used Jamaica Pass to the east of Brooklyn Heights would prove a costly mistake as Howe plunged 10,000 men through the pass on the evening of Aug. 26 — attacking the Americans from a weakened rear.

“To my great mortification,” Col. Samuel Miles, who commanded the Pennsylvania militia rifle regiment above Flatbush, later wrote, “I saw the main body of the enemy in full march between me and our lines.”

The Americans, fighting a hapless rearguard action from hill to hill, writes Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and historian Rick Atkinson in his trilogy series “The British are Coming,” had barely slowed the British assault.

By 8:30 a.m., Howe, Gen. Henry Clinton and Gen. Charles Cornwallis were a mere 2 miles from the main rebel defenses in Brooklyn.

“From this instant,” Clinton reported, “the enemy showed no disposition to stand.”

The Hessians, led by Gen. Leopold Philip Von Heister, had launched an assault against Gen. John Sullivan and his men to the south, while the redcoats, under Gen. James Grant’s command, attacked Gen. William Alexander, also known as Lord Sterling, in the southwest on the Heights of Guan.

The patriots, although fighting feverishly, were surrounded.

Upon realizing that the main British force had come through the Jamaica Pass and would soon surround him, Sullivan ordered his men to retreat to Brooklyn Heights before he himself was captured, according to Mount Vernon.

Stirling and his men managed to hold off the British for several hours but, like Sullivan, realized he was surrounded. Reduced to less than 1,000 men, Stirling detached 400 Maryland soldiers to fight as a rearguard, giving his remaining men a chance to flee.

It was at the Old Stone House, along the Gowanus road, that Stirling and his remaining contingent of men gave the British their fiercest fight of the day.

Fighting surged back and forth before Hessian and grenadier reinforcements obliterated the American line. More than 250 of the 400 men were either killed or captured, including the wounded, lupine Stirling who eventually surrendered to Heister.

According to Atkinson, Lt. Enoch Anderson of Delaware, who escaped by wading to his chin past a milldam despite a bullet wound in the neck, wrote simply, “A hard day this.”

Miracle of deliverance

Washington watched helplessly from the elevation of Cobble Hill as the carnage unfolded around him.

In the aftermath of the battle, a furious John Adams concluded in a letter to his wife, Abigail, that, “In general, our Generals were outgeneraled.”

He was right to a degree. According to a report from Howe, 1,097 Americans were taken prisoner, including three generals, three colonels and four lieutenant colonels, plus 32 cannons seized. Some 300 Americans had been killed, while 700 were wounded.

In contrast, the British and Hessians reported combined losses of 64 killed and 293 wounded.

In the weeks and months leading up to the battle, Washington had failed to recognize that the key to holding New York proper was through Long Island. A weak, divided army that lacked naval power could have never held its own against the British.

In fact, it was only through the divine fate of a northeastern breeze that kept Howe’s “men-of-war from sailing up the East River, where they could have butchered the rebel flank with broadsides,” writes Atkinson.

For their part, the British — on both sides of the Atlantic — were jubilant.

“If a good bleeding can bring those Bible-faced Yankees to their senses,” wrote British Gen. James Grant after the battle, “the fever of independence should soon abate.”

While American Lt. Col. Daniel Brodhead charged, “Less generalship never was shown in any army since the art of war was understood.”

The Americans were pinned to their last toehold in Brooklyn Heights with the British on three sides and the East River to their back. Roughly 9,000 men were packed within 3 square miles, encircled.

Howe, however, ordered a pause. He hoped to avoid a frontal assault against the cornered Americans, as the echoes of Bunker Hill played in his head. Assault trenches were ordered to be dug — less than 1,000 yards from the American encampment.

The eerie sounds of shovels and pickaxes being dug into the earth could easily be heard by the battered patriots, but the British did not yet come.

Washington was not about to miscalculate again.

Fortuitously, the providential northeast wind did not abate, preventing the British from blocking the East River and severing the American line of retreat from Brooklyn.

At 5:00 p.m. on Aug. 29, Washington and eight of his generals unanimously concluded that an evacuation was the order of the day.

Orders swiftly went out to collect what “could be kept afloat and had either oars or sails,” all up and down the shores of Manhattan.

Within a few hours fishermen and civilian sailors answered the call: More than fifty rowboats, scows, periaugers, sloops and schooners converged along Brooklyn’s banks, joined by 10 flatboats, according to Atkinson. One grateful patriot described them as “hardy, adroit, and weatherproof.”

America’s “little ships” had arrived to ferry its standing army to safety.

The very night that orders went out to evacuate, civilian rescuers began rowing boatloads of weary, terrified soldiers to the wharves — and safety — around Fly Market wharf in Manhattan.

Their oars, muffled with rags to quiet their approach, churned against the temperamental currents of the East River.

Orders went out to not talk — or even cough — so as to not alert the enemy of their plan. Yet men, fearful of being left behind, began to crowd the riverbank, pushing to be among the first evacuees.

“An officer,” writes Atkinson, “later reported that Washington himself lifted a huge stone above an overloaded skiff and threatened to ‘sink it to hell’ unless order was restored.”

Control was roughly restored by the 14th and 27th Massachusetts Continentals, who began to methodically withdraw men from Brooklyn’s banks.

By early Friday, vessels were able to ferry 1,000 soldiers an hour.

At 2:00 a.m. an auspicious fog rolled in off the water, further concealing the American efforts.

“I could scarcely discern a man at six yards’ distance,” Lt. Benjamin Tallmadge would later write.

As dawn approached, the last of the regiments left Brooklyn Heights.

“We very joyfully bid those trenches a long adieu,” Tallmadge continued.

Just before daybreak, the British began to sense a change, noting that American sentinels had abandoned their posts.

Swiftly organizing a patrol, the British edged towards the American camp.

“I was the first person in the works,” wrote Capt. John Montresor, “but found the enemy gone except for some entrenching tools, a few cows and horses, and three plundering Yankees who had lingered too long in the camp.”

The last of the American boats, one of which was carrying Washington, was still faintly visible to the British through the morning fog. In vain, the British shot after them but they were no more than fruitless parting shots — by then the boats were too far out of range.

The 9,000-strong American army, despite being beleaguered and unorganized, had been, like Churchill would note in 1940, plucked “out of the jaws of death and shame, to their native land and to the tasks which lie immediately ahead.”

The Americans had lost the battle. They would win the war.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here