“Tight group, Sam!” His was actually a stellar knot: three bullets in a one-hole chain. Better than I’d done. But not as unusual as we’d expected. This Springfield Waypoint in .270 was poking half-minute clumps with many of the loads we fed it.

I swapped the spotting scope for another turn at the rifle.

The .270

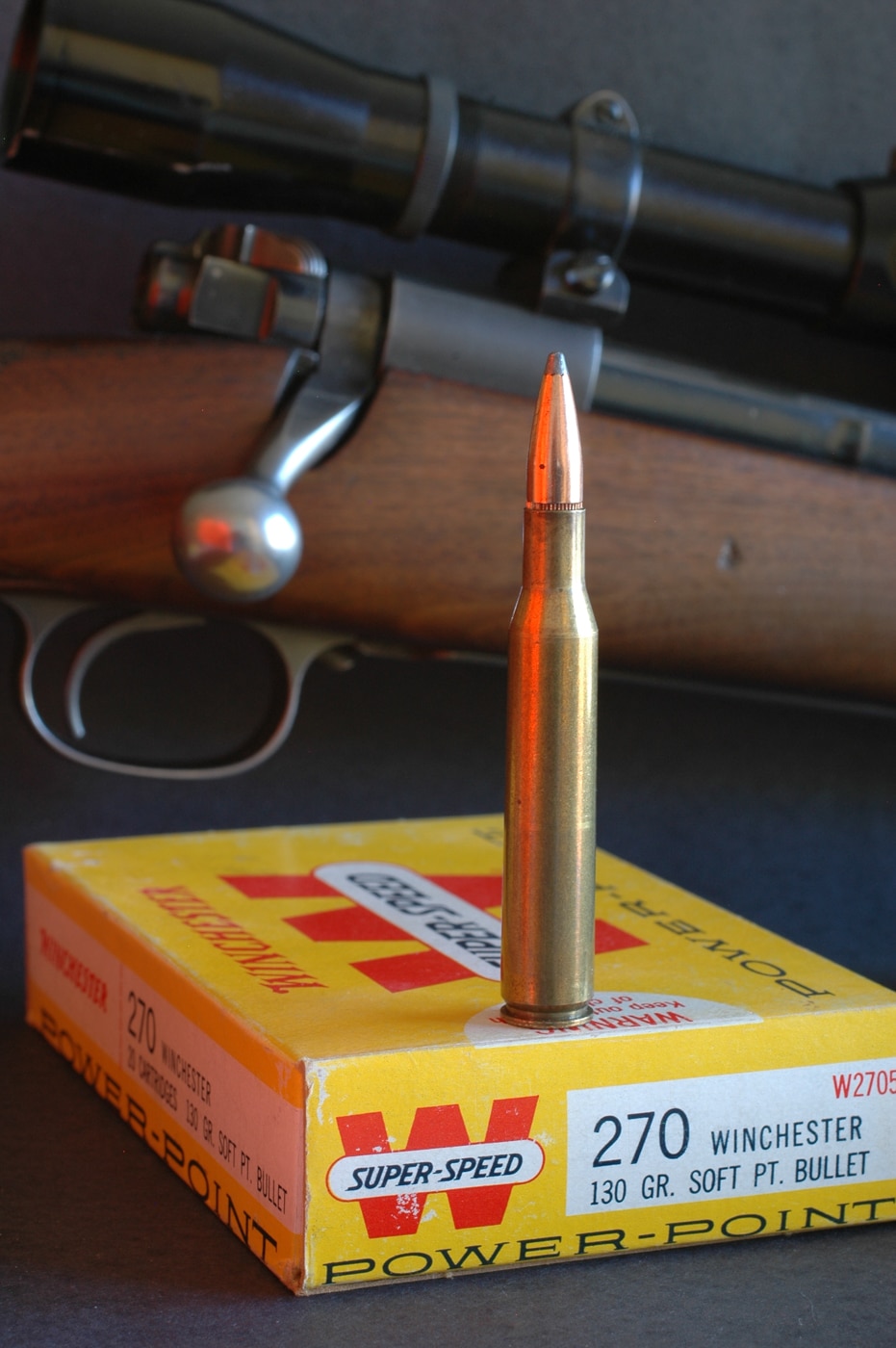

This cartridge was not yet halfway through its first century when it downed my first western big game. Fifty hunting seasons later, it’s still a favorite. While the ranks of able “deer cartridges” have since swelled, none, in my view, has trumped the .270. A fit for any rifle action designed for the .30-06, it hurls 130-grain bullets at Mach 3. They bring over a ton of energy past 200 yards on flat arcs. Given a 200-yard zero, drop at 300 is just 6”. But for all its ballistic zip, the .270 won’t beat you up. Recoil from an 8-lb. rifle is about 17 ft-lbs, 15 percent less than the bump of 180-gr. loads in a .30-06.

During its long tenure, legions of rifles have chambered the .270. This day, Sam and I were firing one of the latest: Springfield Armory’s Model 2020 Waypoint. It had little in common with the Winchester 54, a new bolt-action that had introduced the .270 in 1925. Now in its fifth year, the Waypoint boasts materials and features unknown before the Depression. At Springfield, they came together in a bolt rifle that has proven its accuracy, function and “shootability” in short-action chamberings. A fresh long action adds the .270.

It was at once a logical cartridge, and a surprise. While its 2.540” case is .046 longer than that of the .30-06, the .270 is essentially a necked-down ‘06, with a .473 rim, 17½-degree shoulder and 1.948” base-to-shoulder length. Receivers and magazines for the .30-06 welcomed the .270.

On the other hand, the choice of a .277 bullet was odd. In 1925 no small arms fired such missiles. The .264 bullets of the 6.5×54 Mannlicher-Schoenauer and 6.5×55 Swedish were champs on battlefields and in game fields world-wide. Ditto the 7×57’s .284 bullet. A 27-caliber missile had no intrinsic ballistic edge over those a tad thicker or slimmer; but it was then unique, thus newsworthy. And it had no ties to cartridges that had bloodied U.S. troops in the Spanish American War and World War I.

To hunters weaned on popular smokeless cartridges of the 1890s — the .303 Savage, .30-40 Krag, .30 W.C.F — the .270’s 130-gr. missiles surely seemed skinny and lightweight. The lethal effect of high velocity impact was yet obscure. Also, a drag on the .270: stacks of surplus 1903 Springfields peddled for a pittance to members of the National Rifle Association. At one time a spanking new Springfield with a star-gauged barrel, the fine N.R.A. sporter stock and a Lyman 48 receiver sight fetched only $40!

Designed for stout bolt actions, the .270 Win was stoked to higher pressures than were its competitors, even the .30-06. At a claimed 3,140 fps, 130-gr. .270’s bullets left the gate faster than 87-grainers from the .250 Savage, and passed 300 yards clocking 2,320. But not all deer hunters swapped their lever-action carbines for .270s. Some early .270 bullets behaved unreliably on game, zipping through without opening or upsetting violently on impact. Lost deer and shredded venison drew the ire of hunters. But when a .270 load with a 150-gr. bullet throttled to 2,675 fps appeared, it didn’t sell.

Strangely, the .270 got a lukewarm welcome from the outdoors press. Ned Crossman and Field & Stream’s Paul Curtis paid it little attention. According to Jack O’Connor, Outdoor Life’s shooting editor from 1942 to ’72, his predecessor ignored the .270. Not until its third year did American Rifleman deem it worth a feature-length review.

Townsend Whelen and Sport’s Afield’s Monroe Goode thought better of it, but only O’Connor bellowed his approval. Snapping up a .270 at the 54’s debut, he took it hunting and for decades thereafter used the cartridge on a great variety of creatures. His stature as gun guru for OL gilded his early and frequent endorsements. His pet .270s, from rifle-maker Al Biesen, were known world-wide.

Two years after the stock market dive of ’29 sent Winchester into receivership, Western Cartridge bought the company. CEO John Olin kept the Model 54 in the line until the introduction of its famed successor. Of 52,029 Model 54s manufactured, 49,009 had shipped by then.

While the .270 was second only to the .30-06 in sales of 54s, few Depression-era hunters carried new rifles. A 1939 elk hunter survey by Washington State’s Department of Game to get 1938 harvest data also netted cartridge preferences. The .30-06 was most-named, the .30-30 and .30-40 Krag in its wake, to account for nearly 60 percent of all 2,285 responses. Astonishingly, the 15 most popular cartridges of 44 reported did not include the .270! It showed up just nine times — same as the .44-40 and .22 High Power!

But hunters soon came to their senses. Of 581,471 Model 70s sold before the rifle’s ’63 overhaul, 208,218 were in .30-06, and 122,323 in .270. No other chambering was nearly as popular.

Remington left the .270 off the roster for its first successful bolt-action, the 30A (1921-‘41). But in 1948 it acceded to demand, offering its new Model 721 rifle in .270. Since then, it’s been chambered in almost every hunting rifle bored to .30-06, including single-shots, autoloaders, pumps, even lever-actions.

In my elk hunter surveys of the 1990s, only the .30-06 and 7mm Magnum showed up more often than the .270. Strong “controlled-expansion” bullets helped it drop heavy beasts. In Wyoming in 1944, O’Connor killed an exceptional elk with a handloaded 160-gr. Barnes bullet jacketed with copper tubing. He then “used the .270 for elk almost exclusively.”

I’ve seen a number of elk killed with .270s. Late one afternoon, a client and I caught up with a bull we’d been tracking. It eased from shadows, ivory-tipped antlers rocking with each step. At the strike of a 140-gr. Hornady, the elk reared like a horse, then fell back, planting its tines in the earth, belly up and dead. A ranger culling elk for Colorado’s Division of Wildlife reported his .270 routinely delivered clean kills, adding that its mild recoil enabled him to keep shooting accurately.

Model 2020

Springfield Armory’s Model 2020 Waypoint was introduced that year in 6mm Creedmoor, 6.5 Creedmoor, .308 Win. and 6.5 PRC — all short-action cartridges. The new long-action Waypoint is barreled not just to .270, but to .30-06, the 7mm and .300 PRC and the 7mm Remington and .300 Winchester Magnums. Some chamberings are available in fluted stainless barrels, all in BSF carbon-fiber (CF) barrels with Springfield’s Radial Brake.

It was Sam’s first outing with a Waypoint, but not mine. I had snagged a 6.5 PRC with CF barrel early on. The hand-laid CF stock by AG Composites wore Ridgeline finish. (Another version of that stock has an adjustable comb; both also come in Evergreen camo). A 2.5-10×45 Leupold on the rail brought the weight of that Waypoint to exactly 8 lbs. Its first three shots after zeroing drilled a .62 knot with 147-gr. Hornady ELD Match bullets clocking 2,910 fps. Following groups mic’d .63, .70 and .82. Average measure: .69, comfortably inside Springfield’s .75 standard.

How would this .270 measure up?

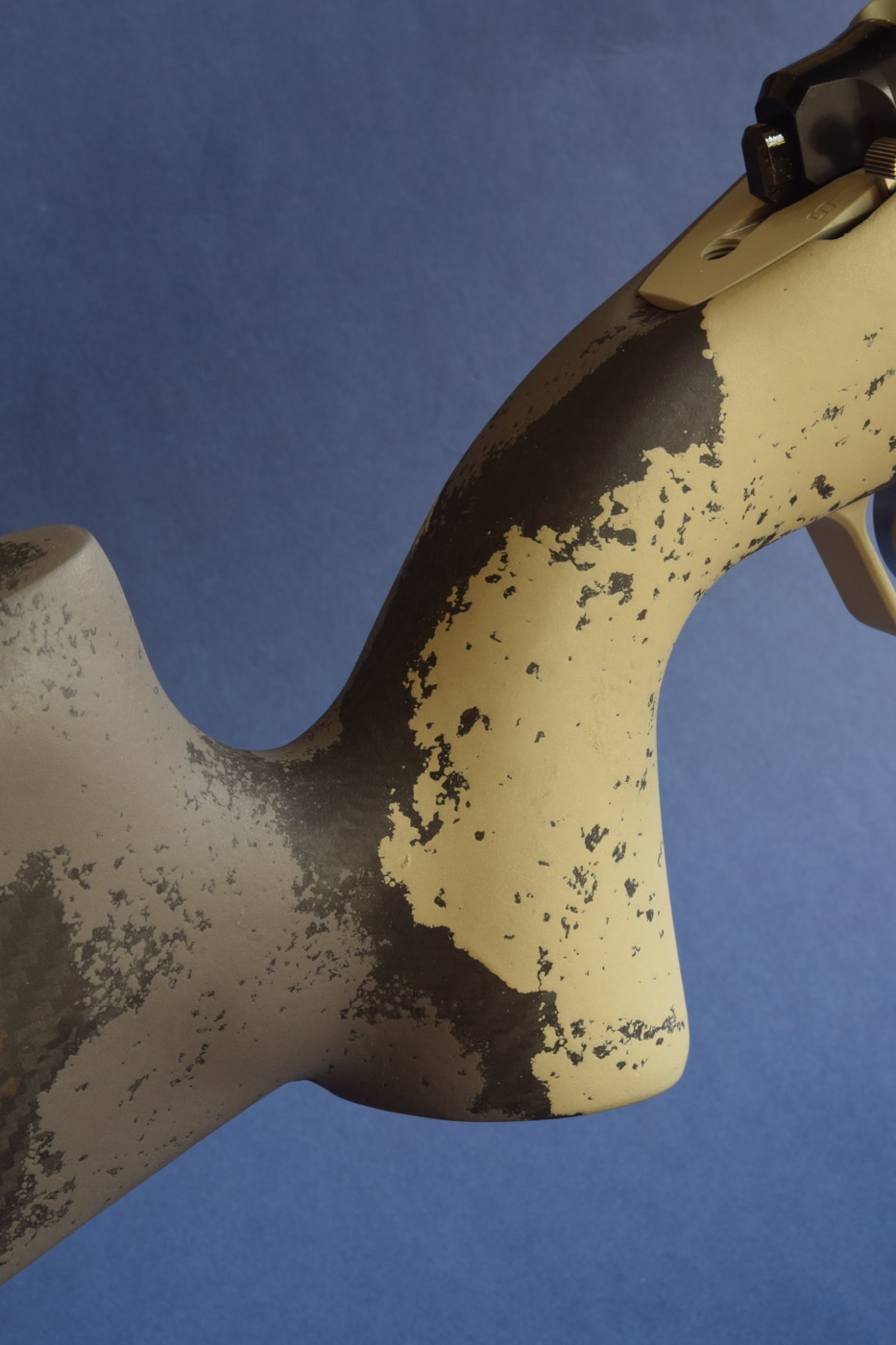

Known for its celebrated M1A rifle, a civilian rendition of the M14 infantry arm, Springfield built the Waypoint to excel as a hunting rifle and a long-range match rifle. Old-timers couldn’t have imagined a sporter with the Waypoint’s steep grip and tall comb, its three M-Lok slots in the fore-stock’s belly and five QD swivel cups.

On the other hand, even shooters who remember black-and-white television and 22-cent gasoline can appreciate a sub-seven-pound rifle guaranteed to shoot into 3/4 MOA. Its pillar-bedded CF stock scales 1 lb., 15 oz. with a standard comb, 2 lb., 11 oz. with an adjustable cheek-rest. A black, 1” Pachmayr Decelerator pad is standard.

The Waypoint action, built by Springfield Armory, has a Remington Model 700 footprint so will accept stocks and triggers for the 700. Not that you’ll want replacements. The rifle’s TriggerTech trigger adjusts externally from 2½- to 5-lb. pulls. A “free-floating roller” yields a smooth, crisp release. The two-position safety permits bolt cycling when “on.” To boost your odds of drilling bullseyes and killing game, Springfield shaved lock time to 1.9 milliseconds — “up to 45 percent faster than the competition.” Exiting, the bullet easily beats your blink.

The two-lug, spiral-fluted bolt glides in races cut in the stainless receiver by Electrical Discharge Machine (EDM). Bolt and receiver are machined after heat-treating so finished dimensions match specs. The twin-lug bolt is nitrided. Its knurled, cylindrical bolt knob is removable, though I find it just the right shape and in just the right place for fast cycling dual cocking cams ease the already-compliant 90-degree lift. You need no tools to disassemble the bolt. The left-flank bolt release is unobtrusive, nicely inletted, silky in its pivot and positive.

The extractor, inserted through a slot in the right-hand (lower) locking lug, has beefy shoulders to hold it securely and resist breakage if a frisky handload sticks a case. The claw is 6mm wide across most of its face, 5mm at its leading edge. Its face angle makes push-feeding effortless. The Waypoint’s plunger ejector is peppy.

Unlike the 700’s separate wafer or washer recoil lug, the Waypoint’s beefier lug is integral with the receiver ring. A five-shot, AICS-style single-stack magazine feeds smoothly and reliably. It’s securely held but easily released by a guard-bow latch. Four 6-48 screws and two recoil pins snug a Picatinny top rail that’s long enough to space any scope rings. Receiver, bottom metal, barrel shank and muzzle brake are Cerakoted.

Both button-rifled BSF CF barrels and fluted stainless barrels are threaded 5/8-24. According to Springfield, each BSF barrel is “jacketed in a roll-wrapped carbon fiber sleeve and loaded under tension [so 95 percent of the sleeve] doesn’t contact the barrel, providing cooling air gaps.” Core fluting reduces weight and boosts surface cooling. Most twist rates favor the long, ballistically efficient bullets that excel at long range.

Here’s a snapshot of barrel lengths and rifling twist for the Waypoint 2020 series:

Short Action

- 6mm Cm, 1-7.5 twist, 20”

- 6.5 Cm, 1-8 twist, 22”

- 6.5 PRC, 1-8 twist, 24”

- .308, 1-10 twist, 20”

Long Action

- .270, 1-10 twist, 24”

- 7mm Rem. Mag., 1-8 twist, 24”

- 7mm PRC, 1-8 twist, 24”

- .30-06, 1-10 twist, 24”

- .300 Win. Mag., 1-10 twist, 24”

- .300 PRC, 1-8.5 twist, 24”

On the bench, the .270 felt as friendly as had the 6.5 PRC. While steep grips limit the hand’s fore-and-aft latitude and with firm palm contact often put my big paw too far forward for right-angle first-joint trigger contact, the Waypoint’s grip is comfy prone, standing and over bags. Generous comb fluting gulps the heel of my hand; a modest flare mid-grip cradles its palm. The 6.5 PRC’s trigger, say my notes, broke at 3¾ lbs. The .270’s releases as cleanly at 3½.

I chose another load, settled the reticle in the Leupold VX-6HD 3-18×44 and fired another group.

“That rifle shoots!” exclaimed Sam, eye to the spotting scope. In fact, this Waypoint was proving as consistently accurate as any .270 I recall in 50 years of firing dozens of rifles so chambered, domestic and foreign. Many had punched occasional knots worth a photo, but very few had delivered sub-3/4 MOA precision routinely with a variety of loads. Herewith a summary of three-shot groups from the Waypoint, fired off sandbags at 100 yards. A Garmin Xero1 C1 Doppler chronograph recorded velocities.

Conclusion

Had Springfield’s long-action Waypoint had been available in 1925, the .270 might have gained its celebrity sooner. Retail price for this extraordinary pairing is $2,599.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Read the full article here